In 1951 Tibet was incorporated into the People’s Republic of China by the Seventeen Point Agreement. Today the legal status of Tibet remains a matter of contention between the PRC and the Tibetan-Government-in-Exile. Both rely upon on legally ambiguous British engineered treaties to make their case.

The inconsistent representation of Tibet’s status in treaties is not, however, a reflection of the ambiguity of Tibet’s status itself; it is a reflection of the ambiguity of such treaties in the context of the positivist-colonial encounter.

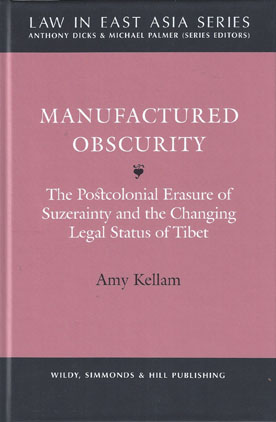

Drawing upon British Government archives, this book examines the issue: to what extent, in what ways, and with what effects has the British imperial legacy in the region converged with Chinese formulations of law and governance in Tibet to prejudice understanding of Tibet’s legal status. This addresses a significant gap in international legal literature, which seldom discusses Tibet outside of considerations of minority rights within the PRC.

This book argues that an assessment of imperialism and its relationship with nineteenth century international law is essential to explaining the events of 1951, but it is only through a reassessment of the postcolonial that the absence of discussion of Tibet’s status in international legal discourse can be explained. The history of Tibet’s legal status highlights contradictions embedded within modernity and exposes the mythological foundations of the modern secular state’s narrative of progress.

Manufactured Obscurity concludes that the much emphasised clash between Western and East Asian values in the field of international law in truth operates along a much narrower divide than might be presumed. This is best assessed as a reflection of the contradictions inherent to the postcolonial within international law; involving both a pushing away of the imperialistic past and a reaffirmation of its continuity in order that modern commitments to the rule of law retain value.