Out Of Print

From the preface

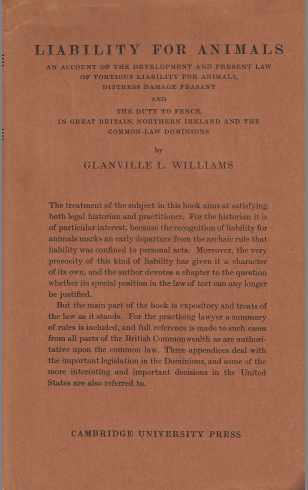

The scope of this work will be found on the title-page; it is a little wider than the short title would indicate. Besides the actions that redress injuries by animals, it takes in the whole of distress damage feasant and such parts of the law of fencing as affect the rules of cattle-trespass.

The book attempts the difficult task of satisfying both historian and practitioner. On the historical side the topic is, I think, a fascinating one. It throws a vivid light on primitive modes of thought, and on the stages by which they were outgrown. It marks a comparatively early departure from the archaic rule that liability was confined to personal acts.

Yet the very precocity of this kind of liability gave it a character of its own; it has not been properly absorbed into the law of negligence. This is because the action of cattle-trespass and the action based on knowledge of an animal’s propensities, though meant to give a rough expression to the idea of negligence, were not in truth actions of negligence.

They antedated the action of negligence, and they might, and still may, impose liability in a case where there was no negligence. Thus a plaintiff at the present day is entitled to choose between an action of negligence and one of these actions imposing strict liability. This adds very much to the complexity of the law. Nor is the complexity confined to the subject of liability for animals, for these same two actions, together with the law of distress damage feasant, have now come to furnish analogies for the creation of new torts of strict liability for extra-hazardous acts.

This development invests the subject with a more general importance, for the law of cattle-trespass and of scienter thus comes to have a bearing on the whole question of strict liability versus liability for fault. I have devoted a chapter to the problem whether strict liability for animals can any longer be justified, and very similar considerations may be thought to apply to torts of the type of Rylands v. Fletcher.

But the bulk of the work is expository, not polemic. For the practising lawyer I have prefixed a summary of rules, and have tried to make the citation of authorities in the notes as comprehensive as possible. Full reference is made to such cases from all parts of the British Commonwealth as are authoritative upon the common law and are not decided solely upon local statutes. In addition there are three appendices dealing with the important legislation in the Dominions. Unfortunately the co-ordinates of space and time have prevented me from paying full attention to decisions in the United States, but some of the more interesting and important have been referred to.

I must acknowledge my deep indebtedness to my mentor, Professor Winfleld, who has given me the benefit of continuous advice and criticism while the work was in progress, besides reading through the final proof. His kindness does not, of course, involve him in responsibility for the views expressed. My thanks are also due to Mr H. G. Meek, of the New South Wales bar, for advice on some points of Australasian law, and to my mother for preparing the index of cases.

G.L.W. St John’s College, Cambridge. 6 December 1938